Below is the text of a sermon that was part of a series, “Eastern Religion.” The second in the series, “Islam” may be found at American Karma as well..

Buddhism

Guest Sermon Delivered July 7, 2002

Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo

Frank Housh

copyright © Frank Housh 2002

Readings

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars

And the pismire is equally perfect, and a grain of sand, and the egg of the wren,

And the tree-toad is a chef d'oeuvre for the highest,

And the running blackberry would adorn the parlors of heaven,

And the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery,

And the cow crunching with depressed head surpasses any statue,

And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels,

And I could come home every afternoon of my life to look

at the farmer's girl boiling her tea kettle and baking shortcake.

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, verse 31

The brain is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will contain,

With ease, and you, beside.

The brain is deeper than the sea,

For, hold them, blue to blue,

The one the other will absorb,

as sponges, buckets do.

The brain is just the weight of God,

For, heft them pound for pound,

And they will differ, if they do,

As syllable from sound.

Poem from Life by Emily Dickinson

The monkey is reaching for the moon in the water,

Until death overtakes him he'll never give up.

If he'd let go the branch and disappear in to the deep pool,

The whole world would shine with dazzling pureness.

The Monkey, a zen koan (anonymous)

One night toward the end of the sixth century BC, a young man named Siddhartha Gotama walked out of his comfortable home in the foothills of the Himalayas and took to the road. We are told that he was 29 years old. He had a wife and a son a few days old, but Siddhartha had felt no pleasure when the child was born.

He had a yearning for an existence that was "wide open" and "as compete and pure as a polished shell," but even though his father's house was elegant and refined, Siddhartha found it constricting, "crowded" and "dusty." Increasingly, he had found himself longing for a lifestyle that had nothing to do with domesticity, and which the ascetics of India called "homelessness."

The thick, luxuriant forests that fringed the fertile plain of the Ganges river had become the haunt of thousands of men and even a few women who had all shunned their families in order to seek what they called "the holy life" and Siddhartha had made up his mind to join them.

Siddhartha's parents, he recalled later, wept as they watched their cherished son put on the yellow robe that had become the uniform of the ascetics and shave his head and beard. But we are also told that before he left, Siddhartha stole upstairs, took one last look at his sleeping wife and son, and crept away without saying goodbye.

It was almost as though he didn't trust himself to hold true to his resolve if his wife begged him to stay. And this was the nub of the problem, since, like many of the forest monks, he was convinced that it was his attachment to things and people that bound him to an existence that seemed mired in pain and sorrow.

Some of the monks used to compare this kind of passion and craving for perishable things to a "dust" which weighed the soul down and prevented it from soaring to the pinnacle the universe. This may have been what Siddhartha meant when he described his home as "dusty." His father's house was not dirty, but it was filled with people who pulled at his heart and objects he treasured.

If he wanted to live in holiness, he had to cut these fetters and break free. Right from the start, Siddhartha took it for granted that family life was incompatible with the highest forms of spirituality. It was a perception shared not only by the other ascetics of India, but also by Jesus, who would later tell potential disciples that they must leave their wives and children and abandon their aged relatives if they wanted to follow him.

Buddha, by Karen Armstrong

Introduction

As we see from the readings, Buddha lived his life as a seeker of religious truth. Although he lived six centuries before Christ, their lives and their teachings bear remarkable similarities to one another. My intention today is to give a brief survey of the Buddhist faith from the perspective of a Buddhist scholar who was raised a Presbyterian and became a Unitarian by default.

I will discuss Buddhism in the context of Christianity, and I will suggest at the end that both of these great world religions have identified the same fundamental religious truth.

First, I will discuss the striking similarities in the development of the religions themselves. Jesus and Buddha were similar both as religious men in their times as well as in the shape of their sacred legacy.

Second, I will detail the core teachings of Buddhism -- the four noble truths, the eightfold path, the law of karma, and the principle of reincarnation -- and their parallels to Jesus' teachings.

Please note that when I discuss Christianity, I mean Christianity as developed by the Roman Catholic Church and mainstream protestant faiths over the last two-thousand years. Although I realize that this is an issue on which reasonable people may disagree, it is from that Christian faith, the one that believes Jesus was the Son of God who died for our sins, that this church and our liberal faith are ultimately descended.

Finally, I will attempt to describe the ultimate spiritual destination of these faiths, Heaven to Christians, and what is known as Nirvana in Buddhism.

Buddhism and Christianity

Buddha and Christ were both said to be the product of immaculate conceptions, and the birth of both was heralded by visits from religious elders who sought the origin of this great foment in the Heavens.

Each has a body of sacred writings devoted to their teachings selected by a council of elders at a critical point in the development of the faith; each faith has suffered a schism, a contentious separation derived from differing interpretations of key religious points.

Both Jesus and Buddha lived a wandering life of ascetic renunciation, and both acquired a body of followers. Each was about thirty years old when they reached a state of religious enlightenment and began teaching others the path to salvation.

At the occasion of each of their deaths, there were stories of great storms and the shaking of the heavens.

After the deaths of both Buddha and Christ, those who adhered to the faith were at first persecuted, then years later the religions themselves became government as kings and rulers converted to Christianity and Buddhism. Monasteries flourished and became the main source of education in Christian and Buddhist societies.

Christianity and Buddhism have each been living faiths for over two thousand years, expanding all over the world, transforming the cultures with which they have contact, and each faith has been itself transformed in turn. Christianity spread from the holy land to Europe and then to the western hemisphere in the last several hundred years, begetting Mormons, Baptists, Quakers, and even Unitarians.

Buddhism moved from what is now northeastern India and spread to Asia, where it came into contact with Confucianism in China and Shintoism in Japan. What came forth was Taoism and Zen Buddhism, each an important school of Buddhist practice, each the product of Buddhist principles at work with the existing pre-Buddhist faith.

In our time, Christianity is spreading rapidly in Buddhist Asia and Buddhism is gaining a steady stream of converts here in the West. Western Buddhism began developing in earnest after the Chinese invaded Tibet, and the priests of that great Buddhist tradition were dispersed, many to our own shores.

The practitioners of both Christianity and Buddhism both seek the intercession of certain venerated, deceased individuals whose lives on the earth have allowed them a spiritual presence enabling them to help the living in their quest for comfort and salvation. In Christianity, they are called saints, and in Buddhism, they are called Bodhisattvas, one who has achieved enlightenment but who has stayed on the earth to teach others.

Each faith has developed a corollary theory of the Trinity. The very name of our church declares our interpretation of the Christian doctrine of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Mahayana Buddhism teaches that a Buddha is a cosmic state of being whose state of achievement can be said to consist of three bodies: the Truth Body of the Buddha's perfect wisdom, the Beatific body of limitless embodiment that constantly reaches out to others, and an Emanation body by which the Buddha can take any material form to appear to other creatures.

Each faith abhors idolatry and each uses rosary beads as an aid to prayer.

The body of both Christian and Buddhist faiths have posed individual women as saints and powerful symbols of compassion. The Virgin Mary is the focus of volumes of Christian prayer, paralleled in Buddhism by Kuan Yin, a young Chinese woman, known as the Bodhisattva of compassion.

Both Jesus and Buddha came at a time of great religious tension. For Buddha, who lived about 600 years before Christ, the ancient religion of his birthplace near the Ganges focused on the sacrifice of animals to God by Brahmin elders. It was a religion that served settled, cattle-based societies and required little from individuals other than submission to the elders who interceded to God on their behalf.

Just as Jesus overturned the tables of the moneychangers, Buddha resented this dominance of individuals' religious life by an elite and concluded that it was each individual's responsibility to cultivate a relationship with a divine presence.

Both religious figures sought nothing short of a reconditioning of the human personality, and each concluded that religious salvation must begin with a surrender of the self to the holy.

Both Jesus and Buddha emerged from a period of seclusion and prayer having been said to have overcome the seduction of the forces of evil. Each then set forth to his followers their fundamental teachings.

Jesus preached his famous Sermon on the Mount, and Buddha emerged from under the Bodhi Tree and articulated to his followers his description of the unenlightened soul -- the four noble truths. He then told them about the way to salvation. He called it the eightfold path. This is what he told them.

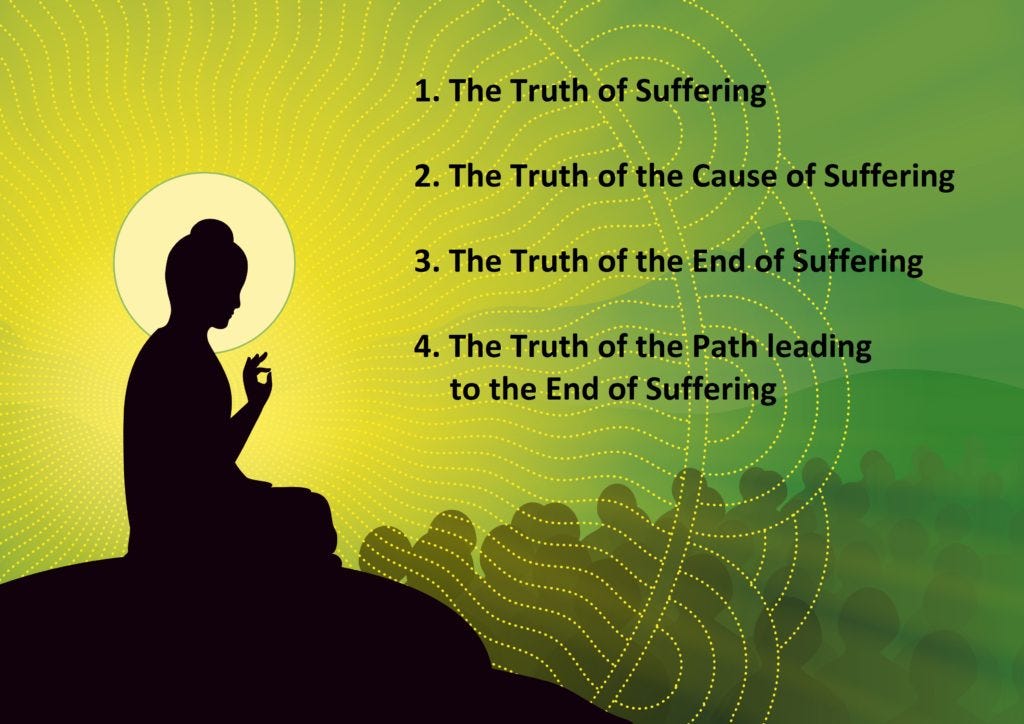

The Four Noble Truths

The first noble truth is that life is suffering. Second, this suffering is caused by desire, craving, or attachment, to things or ideas that are impermanent.

Third, suffering comes to an end when we cease our cravings and attachments. The fourth noble truth is that there is a method to break out of the cycle of craving and rebirth into the a life of suffering, and that is to follow the eightfold path.

The eightfold path describes how individuals must live their lives and practice their faith. Remember that in Buddhism, it isn't about faith in a savior, it's about meditation and religious practice. Faith is merely the means to an end, not an end in itself.

A critical difference between Christianity and Buddhism is that Buddhism does not include the notion of a God-created universe and makes clear that religious epiphany, or enlightenment, can come only after a lifetime or lifetimes of intense, carefully guided religious practice. Enlightenment cannot be achieved by grace, but only by religious dedication.

Karma and The Eightfold Path

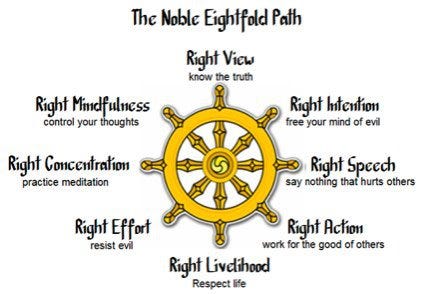

The eightfold path really tells you how to do three things: how to become wise, how to be a moral person, and how to practice your faith.

First, you must become wise -- you must have right understanding and right resolve. You must acknowledge the law of cause and effect, or karma. Put simply, karma means "action", or "cause". For Buddhists, karma is not a psychological construct, but an actual, physical force at work in the natural world in your life at all times. Each act or statement creates a "karmic seed" of effect that will grow and that with which you'll have to live.

Sometimes the consequences of a bad act are immediate -- a harsh word is met with an angry response -- and sometimes the consequences linger. Bad karmic seeds may just pile up and weigh you down -- like the "dust" the young Buddha felt was covering him -- keeping you from enlightenment and within the cycle of births and rebirths.

Accumulate enough bad karma and you cease to be human -- you are doomed to rebirth within a realm of hell. The Buddhists believe in hell, it is just different in that there are many more levels. For Buddhists, you may be condemned to the realm of animals, unable to speak and afflicted to by being used by others.

You may also be in the hell realm of the hungry ghosts, constantly in need of human comforts but not within the human realm to satisfy them. If you want to imagine this, picture the desperate specters of such movies as the Sixth Sense -- you wouldn't be too far off.

You might also end up at the very bottom of the hell realms, one of the eight hot hells or the eight cold hells. As to the hot hell, it may be well described by the lakes of fire that burn but do not consume that Christians are taught is the doomed destination of unsaved souls.

Conversely, there are levels of heaven between rebirth as a human and total enlightenment. If your karma is good enough to break out of the cycle of birth and rebirth, but not quite good enough for total enlightenment, you live in a heaven realm.

Humans live in a heaven realm. This should not be surprising. For all the talk of life as suffering, at its core Buddhism teaches that we must treasure every moment of human existence as extraordinary and beautiful. The Buddha told his followers that receiving a human birth is miracle more rare than the chance that a blind turtle floating in the ocean would stick its head up through a small hoop.

Humans live in a heaven realm because they are uniquely endowed with the ability to understand their situation and the liberty to evolve into something more.

Humans live in the heaven realm with demi-Gods, humans that have progressed, but not yet achieved the status of Gods.

The highest level of heaven is for Gods, but not in the sense of Christian of the term God. For Buddha, the term "God" would only mean a human whose karmic accomplishments allow them to lead long and enjoyable lives. Remember that Gods are still within the cycle of existence, and when the force of those virtuous actions that caused them to be born in that state are exhausted, they suffer through being reborn in lower levels.

Which level of Buddhist heaven or hell in the endless cycle of existence you inhabit is determined by how you live your life, as manifested by your karma at the time of your death.

Objectively, the law of karma is a very simple law, and it's very familiar to us. It's the golden rule we grew up reciting, and the core teaching of the Christian faith. Jesus understood it so well, and he tried to tell his followers that everything we do or say ripples outward into our world of interconnected souls. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Love your neighbor. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer them the other one also. Love your enemies. Do good to those who hate you. Bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.

For Christians and Buddhists, if you act justly and cultivate compassion, good things will happen to you. If your acts are motivated by selfishness and fear, bad things will happen to you.

The eightfold path tells you that to become wise you must both understand this and resolve to become a better person by abandoning harmful mental attitudes -- you must resolve to be less self-absorbed and more compassionate.

After right view and right resolve create wisdom, you must live morally -- three, four, and five on the eightfold path. To live morally, one must have right speech, right action, and right livelihood.

What you say has tremendous potential to heal or harm, and you must be impeccable with your word. Bad speech creates bad karma, good speech cultivates good karma.

You must avoid killing, stealing, and other such harmful activity, and you must find a way to earn a living that is honest and doesn't exploit other people. Jesus seems to recite the eightfold path in Matthew 15 when he denounces the strict codes of conduct imposed by the religious establishment of his day. He says, out of the heart come evil intentions, murder, adultery, fornication, false witness, slander. These are what defile a person, not to eat with unwashed hands (emphasis added).

Finally, to practice religious faith, one must pray with right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration rounding out the eightfold path at six, seven and eight. To achieve enlightenment, you must cultivate positive mental states, live in and fully experience each moment, and learn to focus your concentration inward, seeking liberating insight through meditation.

While Buddhist meditation and Christian prayer are different in many ways, each is motivated in the end by the cardinal virtue of compassion, what Jesus called "love". For Buddhists, meditation on compassion creates the kinship with other souls, leading eventually to the death of the self and the freedom of the soul from birth and rebirth.

This tradition holds a strong parallel in Christianity, and is seen in the prayers for divine intercession that form the core of Christian prayer. The most familiar of all Christian prayers -- the one that Jesus taught his followers to say -- asks God to "forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us." Perhaps Christians are looking for that same strength of faith that allows them to cultivate compassion and free themselves from the chains of the illusion of self. Perhaps this is what Saint Paul meant when he described "the freedom of the Sons of God."

Heaven and Nirvana

For Christians, the nature of heaven is one of the most ethereal of mysteries. The Bible tells us in Corinthians 2:9 that no eye has seen nor ear heard; no mind has conceived what God has prepared for those who love him.

For Buddhists, if you follow the eightfold path, you may eventually lead yourself out of the continuing cycle of births and rebirth and find Nirvana, or enlightenment. Just as the Bible has very little to say about the nature of Heaven to those in on earth, Buddha refused to describe Nirvana to his followers, maintaining that words are not useful to describe this state to an unenlightened person.

A seeming paradox to the notion of Nirvana leading out of the cycle of existence is the Buddhist doctrine of the equality of the cycle of existence and Nirvana. To apprehend this, you must achieve a critical insight known to zen practitioners as kensho, or seeing the nature of the world.

The substance of kensho is the understanding that everything our senses tell us -- everything that we see, smell, hear, taste, and touch -- do not in fact inherently exist. If we remember the zen koan we read earlier -- these sensations are the moon on the water. Like the monkey hanging from the branch, we grasp at them, but they are not real.

All of these sensations are in fact just a reflection in the deep pool. Put another way, they are one with the self -- one with the mind -- one with the collective soul. It's just as Emily Dickinson said -- the brain is wider than the sky, deeper than the sea . . . the brain is just the weight of God.

To quote a Buddhist philosopher:

Both the cycle of existence and Nirvana

Do not inherently exist.

That which is knowledge of the cycle of existence

is called Nirvana.

To conclude this discussion of Nirvana, allow me to quote again from Karen Armstrong:

The attainment of Nirvana did not mean that the Buddha would never experience any more suffering. He would grow old, get sick, and die like everyone else, and experience pain while doing so. Nirvana does not give an awakened person trance-like immunity, but an inner haven which enables a man or woman to live with pain, to take possession of it, affirm it, and experience a profound peace of mind in the midst of suffering. Nirvana is found within oneself, in the very heart of each person's being. It is an entirely natural state, it is not bestowed by grace nor achieved for us by a supernatural savior; it can be reached by anybody who cultivates the path to enlightenment as assiduously as the Buddha did. Nirvana is a still center; it gives meaning to life. An enlightened or awakened human being has discovered a strength within that comes from being correctly centered, beyond the reach of selfishness.

This denial of self is the ultimate religious freedom, and this too parallels our own religious heritage. When Jesus taught his disciples that a grain of wheat had to fall to the ground and die before it could reach its full potential and bear fruit, he was using an image the people of his time and place could understand to communicate this powerful and sublime prescription for religious ecstasy.

Jesus did not mean the destruction of self but rather the ability to see God as one's own true being, fulfilling Jesus' statement at Matthew 16:24 that whoeverloves me, let him forsake himself.

Conclusion

I will conclude with the suggestion that perhaps Jesus and Buddha, the founders of two great world religions, were great and holy men who in their own place and time had the courage to journey to the very depths of the human soul. Each told those around them about their journey and how they, too, could find salvation. The Buddha's message was that to become enlightened you must be wise, live well, and dedicate yourself to the cultivation of a pure heart through religious practice.

Jesus tells us in Matthew that blessed are the pure in heart for they will see God. Actions derived from a pure soul, full of compassion, living in the moment and in the quiet space away from the hue and cry of egotism, this is the ideal of both of the great faiths, the fundamental truth that both embrace.

Buddha tells us that one who acts on truth will be happy in this world and beyond. And as Jesus says, you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.

Final Reading

The Universe is Everlasting.

The Reason the Universe is Everlasting

Is that it Does not Live for Self.

Therefore it can long endure.

Book of Tao, Book II, Chapter 7 by Lao Tse